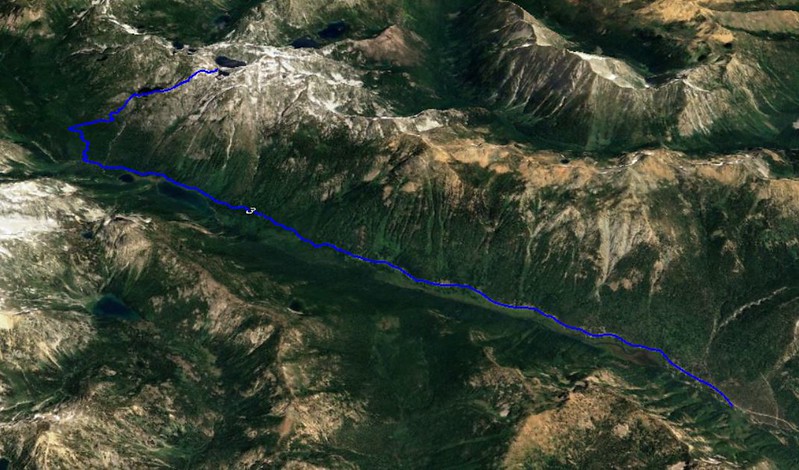

Cle Elum River to Robin Lakes via Cle Elum Valley Road, Hyas Lake, and Tuck Lake

August 9, 2021

1.

I wake in the dappled sun to the sound of laughing water, eat on an ancient log in the shifting light, watch cautiously driven cars stir morning dust on the distant road.

Tiny trout tumble through the river’s gentle waves and I wonder about just staying here, just living here. Just watching the cars come in the morning and go in the evening. Having every night to myself here. Reading my little book, eating my little dinners and breakfasts on the sagging old logs.

I listen to some music on my silly big headphones: Girl in Red, Billie Eilish. The angry girls of this generation are so much better than the angry boys of mine.

I think again of my friends from yesterday, the women and their trucks up on Van Epps Pass. I wonder what they’re having for breakfast. More beer, I hope.

2.

The road’s bright and hot by the time I break camp. Shirtless dudes shout hellos from their Subarus as they pass. A third of the folks offer me a ride, one—a former thru hiker—so insistent that I have to promise her twice I’m not just being polite.

Someone’s placed signs on the empty culverts that sometimes bisect the road, memorializing the creeks that flow less and less these days. “In Memory of Fish Creek.” “In Memory of Skeeter Creek.”

3.

I reach the overflowing trailhead by early afternoon and start up the broad single-track toward Hyas Lake. The trail’s more crowded than the road, full mostly of families with pillows and fishing poles and Dora the Explorer backpacks.

I stop for lunch at Hyas Lake, filter some water and put on some bug stuff. Across the way, three shirtless kids are splashing at each other, laughing so loud it echoes through the whole basin.

4.

The trail stays almost completely flat until Upper Hyas Lake, where it suddenly turns uphill into steep switchbacks. Also, there are hundreds of flies. I spend a disconsolate mile trying to outrun them, then a couple more resigned to my fate, climbing the increasingly steep and eroded trail to Tuck Lake.

The trail braids brutally at the lake, and I wander for quarter hour before finding a strand that goes the way I want, up toward Robin Lakes. Campers sunbathe on the bright white granite, their tents tucked into little bits of loamy dirt between boulders.

5.

From Tuck, the trail’s a thin band of worn rock, marked mostly by cairns and arrows made of fallen wood. It reminds me a little of the old way up Ruckel Ridge in the Gorge: hard, but so beautiful that you hardly notice its difficulty.

After a short mile (and a long thousand feet up), I arrive at the rocky shores of Lower Robin Lake. Three or for groups are camped in the distance, but the place is mostly deserted, and I easily find a perfect spot with trees to shelter from the wind and enough dirt to stake in my tent.

It’s absolutely beautiful.

6.

The rest of the afternoon is a pleasant, bumbling blur of chores and a short walk around the Robin Lakes. Bugs come and go, fading out with the wind, which, by early evening, consistently gusts at 20 or 30 miles an hour.

Dinner’s rehydrated whatever on a tortilla, my stove and I perched on a small ridge overlooking Hyas Lake and Mt. Daniel beyond. Halfway through, I’m joined by a tiny woman in Walmart raingear and badly torn Converse carrying a little food and an armful of maps. She sits down next to me. “I haven’t talked to anyone all day. Do you mind if I join you?” Of course I don’t.

7.

As she eats her snack food dinner, she studies the map, asking if I know the names of various minor peaks. I almost never do. But she names them with aplomb, along with the small streams and shaded glaciers I can barely see.

A storm starts over Mt. Daniel, rain and thunder in the distance, but Cathedral Ridge—as I now know to call it—keeps it at bay, and we sit for half an hour or more, naming the mountains. When my friend—Kelsey—runs out of things she can see, she starts naming the peaks we can’t, the ones just behind Mt. Daniel or on the other side the ridge—Granite Ridge, she tells me—that towers behind us.

Eventually even the unknown is exhausted, and Kelsey stops, a little shy for the first time since we met. “I know it’s stupid.” A long pause. “But I’ve been wanting to come up here for a really long time. And I want to remember the names of all the things.”

“Oh no,” I laugh, “I do exactly the same thing. Something like a third of my memory is taken up with topo maps for places I’ve never even been.”

She laughs too. “I just want to know what to call the places I love.”

8.

Later, in camp, as the wind’s battering the trees that shelter my tent, I think of that line: “I just want to know what to call the places I love.”

Drifting off to a stormy sleep, I wonder about the relationship between loving and naming. Kelsey put it sequentially: she loves these places, and so she wants to know their names. But, as we talked, it got more complicated.

Things didn’t start with love—they never do—but with curiosity. She’d heard of this place, heard there was something here worth seeing, and it was that curiosity that led her here. She knew there was something here to love, but couldn’t love it for herself yet, because she hadn’t yet experienced it for herself.

It wasn’t until actually experiencing it that she could fall in love. And the depth of that experience—the depth of that experience and, in turn, the possible depth of the love that that experience made possible—was in part determined by that prior curiosity. She talked about watching sun on the water, the smell of the warm thimbleberries, even the sound of the bugs flying through the flowers. Stuff I totally missed. And, because she experienced the place more deeply—because her curiosity drove her to experience it more deeply—she could also love it more deeply than me.

That curiosity’s also what led her to wanting to name the mountains and streams and glaciers. And, as with watching the sun or smelling the berries, the naming wasn’t an afterthought, wasn’t something grafted onto a prior process of experience and love. It was part of the initial experience itself, part of the experience that gave her something to love.

Learning the mountains’ names was part of falling in love with them.

9.

There’s an old idea from Troy Jollimore that love is primarily a way of seeing: to love something is to look at it carefully enough to see what’s lovable in it. That’s always seemed right to me, but looking carefully can’t be the beginning, because there must first be something that makes you want to look carefully. Before love, before seeing, before looking closely, there must be curiosity.

As the wind finally sings me to sleep, I take a cue from my new friend and wonder where it came from.

As always, my friend, I am deeply moved by both the power of your observations and the beauty of your prose. Thank you,